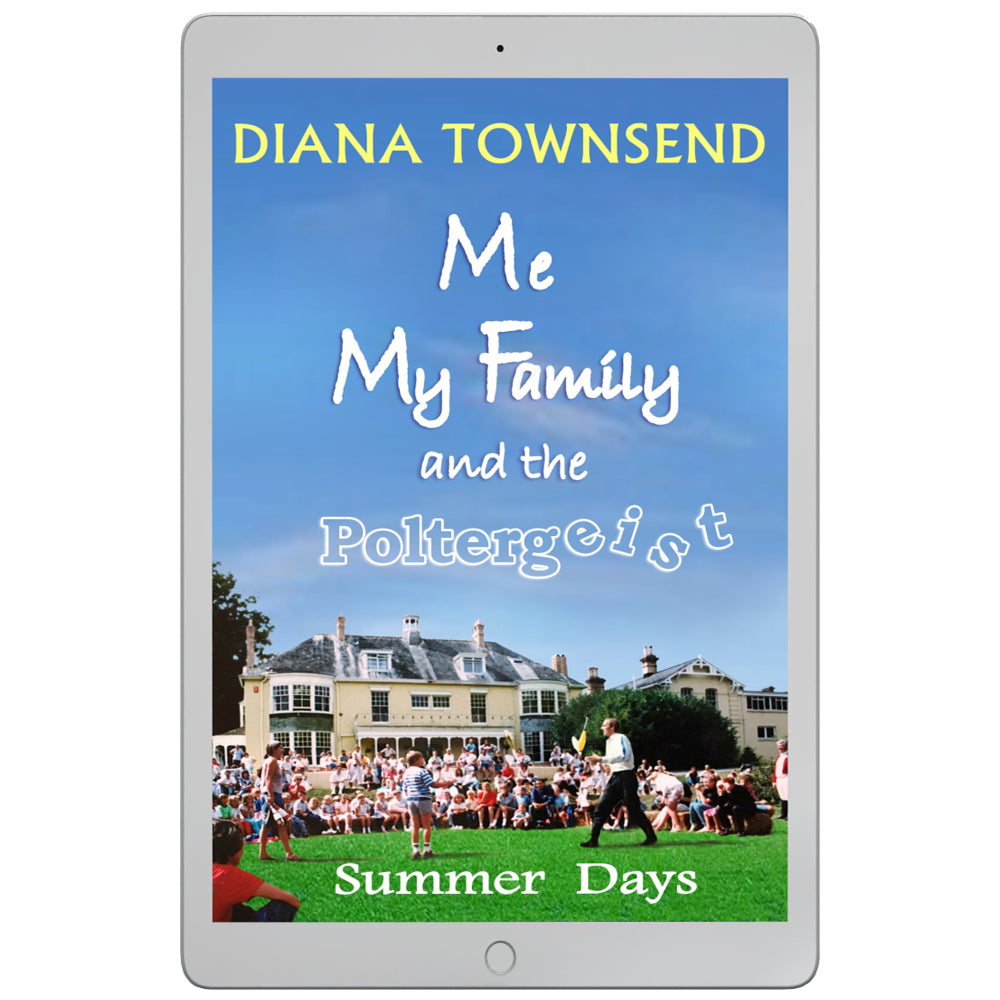

Summer Days (EBOOK)

Summer Days (EBOOK)

Diana Townsend

Couldn't load pickup availability

EBOOK. THE SECOND BOOK IN A SERIES OF THREE MEMOIRS.

An eccentric family. A tourist attraction. And a poltergeist.

After helping her family transform a derelict school into a tourist attraction, Diana Townsend expects to spend her days catering for happy holiday makers.

Instead, she finds herself contending with accident-prone staff, feuding craftspeople, grumpy clowns and an unpredictable ghost called Fred.

Diana believes the family are sharing their home with a poltergeist, but as increasingly bizarre incidents occur, her husband, Bob, becomes convinced someone is playing tricks on them.

When Bob invites a psychic to give demonstrations during a special event, Diana is worried. Is Bob right? Or will the psychic’s performance reveal something unexpected?

Summer Days is the second book in the series Me, My Family and the Poltergeist. Buy it now to enjoy this remarkable story today.

THIS EBOOK WILL BE DELIVERED INSTANTLY by EMAIL by BOOKFUNNEL

Share

How will I get my eBook?

How will I get my eBook?

The link to your eBook will be in your confirmation email. In the unlikely event that you have difficulty downloading your ebook, please email the friendly people at help@bookfunnel.com who will be able to assist you.

Read a Sample

Read a Sample

CHAPTER 1

When I was a child, I overheard a doctor joke that his hospital would run smoothly if only it wasn’t full of patients.

I didn’t understand at the time, but years later, when my family opened a tourist attraction, I discovered what he meant.

“Can you imagine it?” I asked my father as we prepared for our launch. “Won’t it be amazing if we have queues of people waiting to get in?”

“Yes.” He laughed, his face cracking into a familiar grin. “But remember the old saying. ‘Be careful what you wish for.’”

I scoffed. How could having lots of visitors be a problem? We were used to dealing with the public, after all. I was twenty-seven years old, filled with the optimism of youth, and still believed it was possible to achieve anything with enough hard work.

It was the spring of 1987 and the country was preparing for a general election, which Margaret Thatcher would win with a huge landslide. Football hooligans seemed a greater threat than the recently discovered hole in the ozone layer, and despite high unemployment levels, rising inflation, and ongoing troubles in Northern Ireland, there was a general air of optimism.

We had worked tirelessly for months to make sure Silverlands opened on time and, after the excitement of our first weekend, the whole family wanted nothing more than to rest.

It would have been wonderful to lie down and sleep, undisturbed, until the exhaustion inside us faded away, but such a luxury was impossible.

Unexpected expenses had blown our budget, and we had no money left to pay staff except for Martha and Abbie in the tearooms. Instead, we had to face a long summer season fuelled only by adrenalin and the satisfaction of knowing our dreams were still alive.

Gradually, our days settled into a routine.

Each morning was a flurry of cleaning. There were nearly twenty exhibition rooms to prepare, six sets of toilets to clean, as well as three staircases and endless corridors to sweep.

In the giftshop, David, my brother, restocked the shelves while, in the tearooms, my husband, Bob, laid out the counters with cakes and scones, fresh from the local bakers.

David’s wife, Philippa, fed the animals and cleaned the enclosures in the Animal Meadow, while in the main house, Dad and I switched on the exhibitions and made sure everything was running smoothly.

Then, at ten minutes to ten, I would help my mother carry her bags and a supply of leaflets down to the ticket box.

There would often be a few families waiting, but one morning I was surprised to see a mass of mothers and young children crowded around the entrance.

I discovered they were all from the same playgroup in Exeter and had arranged a group visit. Smiling happily, I unlocked the gate and waved them through.

I was about to return to the house when a voice spoke behind me.

“I’m sorry. What was that?” I asked as I turned to face a young woman with a toddler in a buggy.

“Where can I put the buggy?” the woman repeated.

I had no idea.

For months, we had planned every aspect of our exhibitions, but now I realised we had overlooked a few details.

Like buggies.

We had no excuse. Bob and I had Claire, our beautiful, mischievous, two-year-old, and David and Phil had Michael, who was eighteen months. We used buggies every day, and yet they had completely slipped our minds.

I tried to think of a suggestion as I walked beside the woman.

The sun was shining, and Silverlands looked magnificent. The newly decorated walls of the old house were a warm golden yellow with clean white paintwork around the windows and doors. It was barely recognisable as the neglected wreck we had first seen a year ago.

I couldn’t suppress a glow of pride. The transformation really was remarkable.

“Perhaps you can leave the buggy on the tarmac outside the front door?” I suggested, but the woman shook her head. Instead, she heaved the buggy over the threshold and in through the wide doorway.

“I’m not leaving it outside. It might rain.”

Other families followed behind us.

“You don’t mind if I put it at the bottom of the stairs, do you?” she asked. “There’s plenty of room.”

I didn’t argue. The entrance hall was wide and spacious. A few buggies wouldn’t cause a problem.

* * * * *

Two hours later, I stopped abruptly half-way down the stairs. Ahead of me, the entrance hall was packed with buggies. Parents and toddlers squeezed between them, laden down with bags of nappies and baby supplies.

I picked my way through the chaos, pushing the buggies into line against the wall, but as soon as I cleared a path, new families arrived with more buggies.

It was a losing battle, and glancing at my watch, I saw I should have been in the kitchen helping prepare for the lunchtime rush.

I ran to the gift shop, hoping David might be free to help, but he was serving a queue of people while Philippa was busy selling brass ornaments.

Pulling a walkie-talkie from my pocket, I called my father.

“Can you spare a minute?” I pleaded. “There’s gridlock in the entrance hall.”

“OK, I’m on my way.”

“Thanks, Dad.”

In the tearooms, Martha was slapping scones onto plates, her lips pursed into a tight line.

“Are you OK?”

“Aye, I’m fine,” she answered through gritted teeth, her Scottish burr harsher than usual, “but Abbie left her brains at home this morning.”

“What do you mean?”

“Look in there. You’ll see.”

I stepped into the kitchen and gasped.

When we opened Silverlands, we had acquired an industrial-sized dishwasher from another attraction that was closing down. Now it was hidden from view beneath a billowing mass of bubbles that swayed gently as they slid down its sides and spread across the floor.

“What’s happened?” I demanded.

“I’m sorry.”

Abbie was scrubbing dishes in one of the steel sinks, her brown eyes huge and anxious.

“But what’s happened?” I repeated. “What’s wrong with the dishwasher?”

“It’s gone mad. I can’t stop it. There’s suds coming out everywhere.“

“I can see that! How many tablets did you put in?”

Abbie dropped her head and dark hair hid her face as she mumbled something.

“What was that?”

“There weren’t any tablets left, so I put in some washing-up liquid.”

“Abbie! There’s a new packet of tablets in the storeroom. Why didn’t you ask me?”

“I didn’t want to disturb you. I knew you were busy…”

“How much did you put in?”

“Just enough to fill the tray where the tablets go. I wanted to make sure everything was clean.”

I jumped as Martha’s voice rang out behind me.

“If no-one’s going to collect the orders, I’ll have to bring them through myself, won’t I? There’s four families waiting when you’ve finished playing bubbles.”

Slapping the orders on the work surface, she stalked out.

* * * * *

Dad arrived soon afterwards.

“That’s cleared the gridlock…” he began, then stopped and gazed at the mounds of foam creeping across the floor.

“What the hell’s going on?”

“Abbie put washing-up liquid in the dishwasher. Any suggestions?”

“Sack her.”

“Any helpful suggestions?”

“Don’t worry, I’ll deal with it.”

He disappeared and returned a few minutes later with a shovel in one hand and a clutch of buckets in the other. Bob followed him.

“Oh, my God! I see what you mean.”

“Teapots!” Martha’s voice rang out from the servery. “I need more teapots!”

“Where are they?” I asked Abbie, but I already knew the answer.

As if on cue, the dishwasher wheezed to a halt.

Bob and I looked at each other. The steel-edged cube that formed the lid of the washer was more than a metre in each direction. Normally, it was possible to see the rotating steel sprayers and the clean crockery inside, but now it was completely filled with foam.

“Don’t open it,” Bob warned me.

“But we have to. There’s a queue of people waiting.”

“If we put it through another cycle with just water, it might get rid of the bubbles.”

“But that will take fifteen minutes. We can’t wait that long.”

“You two argue it out,” Dad said. “I’m going to clear tables. There must be some teapots we can wash in the sink.”

“You might as well open it,” I urged Bob. “It can’t get any worse.”

“OK, but don’t say I didn’t warn you,” he muttered.

He slid the lid up, and for a long moment, the huge cube of bubbles quivered in the air, then, very gently, collapsed.

“I told you,” Bob said as a foaming tidal wave oozed across the kitchen, covering our feet and forming drifts against the cupboards.

“It’s like those foam parties they have in Ibiza, isn’t it?” Abbie giggled.

Dad appeared in the doorway with a tray loaded high with dirty dishes. Seeing the white expanse covering the floor, he roared with laughter until the cups rattled on the tray.

“You opened it then,” he gasped.

“It’s not funny!” I wailed, ploughing through the remaining bubbles, searching for the teapots.

“You’re right,” Dad agreed, still chuckling. “This is serious. There’s a massive queue at the counter, Martha has a face like thunder, and all the tables need clearing.”

“I’ll do the tables,” Bob offered and hurried through into the tearooms, leaving a trail of frothy footsteps behind him.

“Here.” I found some teapots and handed them to Dad. “Can you rinse these and get them out to Martha?”

“Sure,” he nodded. “You go on preparing the meals. Don’t worry, we’ll have everything under control in no time.”

* * * * *

There were still bubbles lurking in the corners of the kitchen when we closed at six o’clock.

Martha had never caught up with the queue of people waiting to be served, and the lunchtime rush had blended with the afternoon tea rush.

Dad hadn't had a chance to release Mum from the ticket box for her lunch break, and by the time we closed, everyone was exhausted.

As usual, we gathered for a cup of tea while Mum counted the day’s takings.

“That was a disaster!” I sighed as I sat Claire down with a bowl of macaroni cheese. I felt guilty that I had barely seen her all day while she had been behind the counter in the gift shop playing with Michael.

“Not a complete disaster,” Mum corrected me. “We took a lot of money.”

“But it was chaos. We have to do better.”

“Yes,” Bob agreed. “Martha wasn’t happy. We don’t want her walking out on us. That really would be a catastrophe.”

“Don’t even talk about it,” I groaned.

I had already come to depend on Martha’s calm head, and the thought of coping without her scared me.

“We ought to sack Abbie, though,” Bob said.

“No!” I protested. “It wasn’t her fault. She was only trying to help, and she does work really hard.”

“I can’t see why you defend her. The girl’s an idiot.”

“No, she’s not. She just needs clear instructions.”

Bob shook his head in disbelief.

* * * * *

The next morning, as I vacuumed my way through the upstairs exhibition rooms, David stuck his head around a door.

“Spare a minute,” he said, and disappeared.

“What is it?” I asked. He didn’t answer, so I hurried behind him to the other end of the building.

“I need to finish cleaning,” I protested, but David held the door to Devon Mysteries open and waved me inside.

“Notice anything?”

The Devon Mysteries exhibition was housed in four large rooms that had once been classrooms. It contained scenes from macabre west-country legends and displays about mythical creatures such as the Beast of Bodmin.

“Something stinks, doesn’t it?” David asked.

He was right. A rich and deeply offensive aroma permeated the air.

“Where’s it coming from?” I asked.

“No idea. I’ve been trying to track it down, but it seems to be everywhere.”

I turned around, sniffing as I went.

“Is it this bad in the other rooms?”

“See for yourself.”

The exhibition was laid out along a twisting path, so visitors discovered strange scenes and apparitions at every turn.

To add to the eerie atmosphere, flickering green spotlights illuminated the displays and a soundtrack of moorland winds moaned in the background.

I walked through the semi-darkness, sniffing as I went. My eyes watered as the foul smell wafted around me, but I still couldn’t tell where it was coming from.

“Did you notice it last night, when you switched off?” I asked.

“No, but to be honest, I was so shattered by the time we closed I wouldn’t have noticed if the place was full of elephant poo.”

“Is that what you think it is? Elephant poo?”

“Of course not, but it does smell a bit like poo, doesn’t it?”

He was right.

“Maybe people will think it’s intentional. That it’s all part of the atmosphere. You know, that it’s supposed to stink like a graveyard with rotting bodies.”

Even in the darkness, I could see the offended look on David’s face.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” he snapped. “We have to find out what’s causing it and we haven’t got much time. You go that way, I’ll go this.”

I prowled around again, nose twitching, until David’s voice rang out from the next room.

“Blooming Hector! That’s disgusting!”

I found him leaned against a wall, an arm across his face.

“What is it?” I demanded, but he only pointed into a corner.

From the horror in his voice, I had expected to see a rotting corpse, but, as I glanced down, I could see nothing. Finally, as I peered more closely, I noticed a gap between the skirting board and the base of a display case. Something pale protruded through the gap.

“What is it?”

“No idea.” David’s hand was still over his face. “I tried to pull it out, but it was like being gassed.”

Holding my head to one side, I poked the pale object with my finger. It was smooth and flimsy and bent when I touched it. Reluctantly, I grasped it between my finger and thumb and pulled.

Slowly, accompanied by a gut-wrenching stench, the object slid out from behind the display.

It was an overflowing baby’s nappy.

“Oh my God!”

The nappy slipped from my fingers and squelched onto the floor.

“I’ll get some disinfectant.”

“And air freshener,” David suggested, “lots of air freshener.”

“Open all the doors. I won’t be long,” I shouted over my shoulder as I ran through the house, trying not to panic. There were only minutes left until we were due to open and the vacuum cleaner was still standing, abandoned, in the middle of the Down in Devon exhibition.

Abbie was in the kitchen preparing sandwiches.

“Leave those for now,” I ordered. “Finish cleaning upstairs. I’ll be back as soon as I can.”

Armed with a bucket and an assortment of cleaning materials, I rushed back to Devon Mysteries. As I arrived, David was waving his jumper through the entrance doorway.

“I thought it might disperse it a bit,” he explained.

“Here.” I threw a can of air freshener at him. “Use that. All of it.”

A moment later I was splashing disinfectant over the brown marks staining the bottom of the display case.

“How can people be so disgusting?” I fumed.

* * * * *

I was still seething when we closed that evening.

“It’s not funny,” I protested. “We’ve got a lovely baby-changing room. It’s not too much to expect people to use it, is it?”

Dad chuckled at me.

“You look about twelve-years-old when you’re indignant. Did you know that?”

I frowned at him.

“I’m being serious.”

“I know you are, love, but it’s the joy of dealing with the public, isn’t it? Most of them are great, but there will always be a few that make you want to kill them.”

“I suppose so,” I grunted.

“I told you to be careful what you wished for.”

He grinned at me. “The problem with tourist attractions is that they attract tourists.”

“But we need tourists,” I protested. “Loads of them.”

“Of course we do, but you like it much better when they go home, don’t you?”

“That’s ridiculous,” I sniffed, but we both knew it was true.

* * * * *

Mixing with people has never come easily to me. I have always been the observer, the quiet one in the corner who would rather listen to other people’s conversations than join in myself.

Fortunately, the rest of my family love nothing more than entertaining people.

Bob is a natural performer. His mother was an actress, and he spent much of his childhood backstage in a theatre or watching her shows from a spare seat in the auditorium.

He should have been a performer himself, but his father had different ideas and he succumbed to pressure to follow a more traditional career – at least until he met me.

At Silverlands, he was in his element. The circus was a big theme in our attraction and Bob took on the role of ringmaster, welcoming visitors with a wide smile, a red coat and a raised top hat.

David never tired of chatting to visitors, and Philippa welcomed families to the Animal Meadow with a friendly smile.

I tried hard to follow their lead, but I never really succeeded. Painfully shy, I felt awkward talking to people, and I was always afraid they sensed it.

In the tea rooms, I tried to smile all the time, then worried I was smiling too much. I didn’t mind working hard. I could wash dishes or clear tables from dawn to dusk without a break, but I found speaking to people terrifying.

Sometimes I found excuses to avoid the visitors. If there was a problem with one of the displays, I was the first to volunteer to sort it out. Our main attraction was Silvers Model Circus, the incredible, animated model my father had started building long before I was born. It ran on an intricate system of belts and pulleys which needed to be tensioned and lubricated at regular intervals. I offered to share the maintenance with Dad and spent many happy hours laying under the model dripping oil onto the miniature bearings.

“Hiding again?” Dad would say as he saw me emerge from under the circus platform.

“Of course not,” I lied. “I’ll be in the tearooms soon, but I really must pop down to the office first and get the VAT returns finished.”

But I always made sure to be back in the tearooms in time for the lunchtime rush. Once a queue formed at the counter, I could stay in the kitchen preparing meals. It felt safe in the kitchen.

* * * * *

Despite feeling uncomfortable with strangers, I loved the energy that flowed through the house when it was busy. It was exhilarating to hear children’s voices echoing along the corridors and their excited calls as they discovered something new.

The house felt strangely alive when it was full of people, and there was a wonderful atmosphere that radiated everywhere. When the entertainers were performing on the main lawn, the laughter and applause could be heard in the tearooms and the music from the gift shop floated up the main staircase to mingle with the folk songs playing in the Down in Devon exhibition.

Sounds were everywhere. Not intrusive, deafening sounds, but a warm, active buzz like the pulse of a living creature.

I loved Silverlands intensely. It was something we had created from the empty shell of a building listed for demolition, and now it had a character of its own. It was a warm and friendly place and it made me happy to see that others loved it too.

We soon had repeat visitors. Even in our first season, we recognised faces when those who had enjoyed their visits returned.

David spoke to an elderly couple who explained they had three sets of grandchildren and they had brought each set to visit us when they came to stay.

“It’s so lovely,” the old lady said. “I can’t really put my finger on it, but there is something magical about this place. I don’t know if it’s the exhibitions or the gardens or the entertainers, but it just makes me happy being here.”

* * * * *

But not all our visitors were happy.

One afternoon, as I turned a corner, I heard raised voices and found a woman screaming at Bob. His face was a picture of misery and he was scarlet with embarrassment.

“Is something wrong?” I asked.

The woman rounded on me.

“There certainly is! I have never been so disgusted in my life. You should be ashamed of yourselves.”

“Perhaps you can help this lady,” Bob backed away as he spoke. “I really need to be somewhere else.”

The woman switched her attention to me as Bob hurried off.

“I’m going to write to the newspapers about this! And the radio! And the TV! You can’t treat people like this.”

“I’m sorry,” I broke in, “but what exactly is the problem?”

“The disabled toilet! It’s disgusting!”

I didn’t understand. I had decorated the toilet myself. We had specially adapted a large ground floor room and provided all the necessary fittings and equipment. There were cheerful pictures on the walls and it was cleaned regularly. I couldn’t imagine why she was so upset.

The woman grabbed my sleeve and pulled me along the corridor.

“You see for yourself! It’s not decent!”

The moment I stepped into the toilet, I understood.

I had been so concerned with the interior of the room that I had not given a thought to the exterior. The glass in the windows was not frosted.

I was horrified.

The window looked out onto a narrow walkway at the back of the house and the woman told me she had been helping her elderly mother onto the toilet when a man walked past the window and waved at them.

There was nothing I could do but apologise. It had been a genuine oversight, but I felt awful. I refunded the woman’s entrance money, apologised to the old lady and offered them both a free meal in the tearooms.

Later, I caught up with Bob. “Thanks for abandoning me earlier.”

“I’m sorry.”

He had the grace to look ashamed of himself.

“I didn’t know what to say to her.”

“She was right to be upset about the windows,” I conceded. “I’ve nailed a curtain across the window for the time being and left the light on. I just can’t believe none of us noticed.”

* * * * *

After the chaos of the Easter holidays, the children went back to school and our visitor numbers reduced dramatically.

We knew the numbers would go up again as the summer approached, but for a few weeks, it gave us a chance to catch our breath and finish the many tasks we had been unable to finish before we opened.

Without a doubt, the best part of the day was after the visitors had gone. A wonderful peace descended upon the house and gardens, and for a short while, we could relax.

We lifted the children out of their playpens and our dogs, Ossie and Dino, came charging out of the flats, their paws clattering down the stairs as they headed out onto the lawn.

Then Silverlands was ours.

Later, when the children had been fed, played with, and tucked up in their beds, when the shop had been restocked, the displays checked, and everything was ready for the next day, I would take my hoe and go out to weed the flower beds.

I have always loved the special quality of light just before sunset. Those few precious moments when the last rays skim low across the land, outlining every leaf and blade of grass with a magical golden halo.

At Silverlands, the sun dropped below the hills behind the tickets box, sending long purple shadows rolling across the lawns. Robins and blackbirds sang in the treetops and bats appeared to hunt as the day faded to twilight.

I often stayed out weeding until it was too dark to see, savouring the tranquillity and remembering how lucky I was to call such an incredible place my home.

* * * * *

Each day, after we closed at six o’clock, the family gathered for a cup of tea to discuss how the day had gone.

I usually worked in the tearooms in the afternoon so I would get everything ready and finish laying the tables for the next morning as I waited for the others.

One afternoon, Mum and Dad arrived first, Dad lugging an old hold-all with the day’s take from the ticket box. Mum settled herself on the window seat of the bay window and started counting. She entered the figures in a small notebook, then waited expectantly while I made up the tearooms’ till.

“Very good,” she nodded when I told her how much we had taken.

A few minutes later, David appeared from the gift shop with the cash from the tills there.

Once Mum had tallied up the totals, and Bob and Phil had joined us with the kids, we started chatting about what had happened during the day.

“I had a lovely Irish family in the gift shop earlier,” David began. “They were telling me how much they loved the Devon Mysteries. The little boy was giggling his head off describing his Mum jumping at the scary bits. He thought it was the funniest thing he’d ever seen.”

“I know the ones you mean,” Phil joined in. “They were over in the Animal Meadow just before we closed. They had a little girl too, didn’t they? With big blue eyes and no front teeth.”

“That’s them. They’re staying at a caravan park in Paignton and they took some of our leaflets back with them to show the other campers.”

“Excellent. There’s nothing better than word-of-mouth advertising,” Dad beamed.

Claire and Michael were sitting in high chairs. Claire had a bowl of pasta in front of her, but now she upended the lot onto the carpet.

“That’s naughty! Don’t throw your food on the floor,” I scolded her as Ossie and Dino raced across to help clear up.

I slipped behind the counter to grab some kitchen roll and heard a familiar creaking from the corridor upstairs.

Footsteps.

I ignored them.

From the first time we had visited Silverlands, there had always been the sound of footsteps. It had worried me at first, but Bob insisted that all old houses creaked and the builders had joked about a ghost called Fred.

Whenever a tin of paint was spilled or a box of nails went missing, Fred was always blamed. It became a running joke, but as time went on, things happened that were not so easy to explain.

Although I had no proof, at least nothing I could show to other people, I had become convinced the old building was haunted.

Then, one day, a tin of plums disappeared in front of me. One moment it was there, the next it was gone. I had been extremely upset at the time because I knew what I had seen, but I didn’t tell anyone except Dad, as I didn’t think anyone else would believe me.

Mum, Dad and David had all had strange experiences themselves, but Bob was certain Fred was nothing more than a joke played on us by the builders.

Now, as I listened to the distant footsteps, I knew raising the subject again would only end in an argument, so I ignored the sounds and hoped that Fred, whatever he was, would behave himself.

But, as I wiped the last of the pasta from the carpet, I realised the others were listening to the noises too. And it wasn’t just footsteps. There were voices.

David was the first to jump to his feet and head into the hall, with Ossie and Dino close behind him.

“Who’s there?” he called.

The others followed while I stayed with the children, my heart pounding.

I heard Ossie bark and David telling him to be quiet. It was some minutes before Philippa came back.

“What was it?” I asked.

“Nothing to worry about. Just two old ladies. They didn’t realise we’d closed. They were trying to get out, but all the doors are locked.”

I breathed a sigh of relief as the rest of the family returned.

“We’re going to have to be more careful,” Bob said. “Imagine what would have happened if they’d been in the Devon Mysteries when we’d turned the lights off? They would never have found their way out.”

“But I checked all the exhibitions,” David protested. “I don’t understand how we missed them.”

“Did you check the loos?” Mum asked.

“The ladies’ loos?” He sounded horrified. “Of course not.”

“Well, I think we’d better look more carefully in the future,” Mum laughed.

After that, checking the building at closing time became a daily ritual.

As soon as all the tills were emptied, one of us would take up position in the entrance hall while two others, accompanied by the dogs, went upstairs and worked their way through the various rooms.

There were so many twists to the corridors, hidden alcoves and blocked sightlines, as well as thirteen outside doors and fire exits, that it took a full thirty minutes to make sure the house was empty.

* * * * *

As the evenings got lighter, I spent more time outside in the grounds. We had hired a local farmer to cut the grass on the lawns, but the surrounding areas were still heavily overgrown. I longed to clear the blackberries and nettles from the woodland areas so visiting children could explore them, but as we couldn’t afford any gardeners yet, I had to satisfy myself with a putting a row of bedding plants around the edge of the tea lawns and hanging baskets under the verandah.

The weather was beautiful, and it was lovely to see families picnicking on the lawns. Over the May bank holiday weekends, Bob arranged jugglers and entertainers each day, and the crowds loved them.

Everything was going well.

June arrived and the first day of summer brought black clouds and heavy rain.

I wasn’t worried. Silverlands was an all-weather attraction, and there weren’t many of those near us. Our visitor numbers went up, and I had to send a message to the bakers in Chudleigh asking them to send more supplies.

“Are you sure we’ll need all those?” Abbie asked as the extra cakes and scones arrived, but by the end of the day, the tearooms’ counter was empty.

It rained again the next day and the next.

All week, the skies were hidden behind a thick blanket of cloud and we heard from friends who ran a camping site that many of their guests were packing up their tents and caravans and heading home.

We still had plenty of visitors to keep us busy, but now, instead of being spread through the grounds and the Animal Meadow, they crowded into the house and the craft block. Picnics on the lawn were no longer possible, and we found families eating sandwiches in every corner of the house.

In the Animal Meadow, Philippa struggled as the rain turned the ground to mud and the animals huddled inside their houses, looking wet and miserable.

We weren’t the only ones affected by the bad weather. Thunderstorms and hail caused havoc across the country, and the first week of Wimbledon was all but washed out.

Despite the rain and clouds, our visitors were still remarkably cheerful. One afternoon, a man advised me to go and check in the Devon Mysteries.

“I’m afraid there’s a bit of a puddle on the floor,” he said.

Thinking someone had spilled a drink, I sent Abbie up with a bucket and mop, but she came back a few minutes later with wide eyes.

“I think you’d better have a look yourself. It’s a really big puddle.”

She was right. The water stretched from one side of the room to the other and I could hear dripping coming from behind a partition. Unlocking an access hatch, I clambered through to the back of the display and found the whole area behind the partition was several centimetres deep in water.

Waving a torch upwards, I could see drips falling from a crack in the ceiling.

Hurrying back downstairs, I found a bucket to put under the leak. Then I mopped the floor as best I could and apologised to the visitors as I worked. To my relief, they were understanding and simply picked their way through the shallowest parts of the flood.

When I had cleared the worst of the water, I phoned Steve, the builder who had been foreman of the renovations.

“I warned you those roofs were in poor shape,” he said.

“I know, but something’s changed. We used to get the occasional drip, but now there’s a lot of water coming through.”

“OK. I’ll come over first thing in the morning.”

* * * * *

It was still raining when Steve arrived the next day.

He put up a ladder, inspected the flat roof, then came back and shook his head.

“One of the main joints has let go. I’m afraid the whole thing needs replacing. I told you that when I first looked at it.”

“I thought you said it would last for another year.”

“I said it might last for another year if you were lucky.”

I ignored the note of exasperation in Steve’s voice.

“There must be something you can do?”

His eyebrows furrowed as he frowned at me.

“The problem with flat roofs is they’re supposed to be flat. They should only have enough slope for the water to run off, but if they’re built of rubbish materials, like that one, they warp over time and the rain gets caught in the hollows. Once it does that, you’ve got water laying on the roof and it’s only a matter of time before it finds its way through.”

“So, what’s the answer?”

“I told you. A new roof.”

“But that means stripping everything off. We can’t do that while we’re open, can we? Surely you can do something? Just until the end of the season?”

For a moment, I thought he would refuse, but then his shoulders sagged.

“OK, I’ll try again if you insist, but I’m not promising anything.”

Steve spent the rest of the afternoon on the roof and the smell of hot pitch drifted through the rain. Finally, he came down and stood dripping in the kitchen.

“Do you want to borrow a towel?” I offered.

“No, I’m off home for a bath.”

He looked exhausted. His wet hair clung to his head and his hands were black with tar.

“Do you think you sealed the leak?”

He shrugged apologetically. “For now, maybe, but it’s a mess. If that doesn’t hold, I’m afraid there really is nothing else I can do.”

* * * * *

It was only a few days before David burst into the kitchen.

“Phone Steve! Now! The roof’s leaking again!”

I was busy unpacking a delivery of groceries.

“There’s no point,” I said. “He told us there’s nothing else he can do.”

“He has to do something!” David yelled.

“Calm down,” I snapped. “It can’t be that bad.”

“Can’t it? Come and see.”

I followed him upstairs and my heart sank. Water was spraying down from the ceiling like a shower.

David ran a hand through his hair, as he always did when he was stressed.

“We have to close the exhibition.”

“We can’t do that,” I protested.

It was David’s turn to snap.

“Get real, Diana! There’s water spraying over the power sockets. It’s not safe. I’ll find a closed sign. You get everyone out.”

That evening, Dad, David and I met in Devon Mysteries. Dad wanted to see the situation for himself, but David had already made up his mind.

“There’s no alternative. We have to close the exhibition. Steve’s tried everything.”

“Then we need to find another builder,” Dad said calmly.

“What’s the point? They’ll only say the same thing.”

“Can you put the lights on?” Dad asked.

David shook his head.

“It’s not safe. The exhibition will have to stay closed until we can get the roof replaced.”

“We can’t do that!” I objected.

“I told you, there’s no other way,” David shot back.

“Stop shouting, you two,” Dad cut across us. “There’s always another way. Go and find me a ladder.”

By the time David returned with a step-ladder, Dad had opened the access hatch and was standing in the space behind the partition.

“What are you going to do?” David asked as he passed the ladder through to him.

“I don’t know yet.”

Pulling a torch from his pocket, Dad flashed it above him at the ceiling tiles. Then he climbed up the ladder, pushed a tile out of its frame, and climbed higher so that his head and shoulders disappeared into the space between the ceiling and the flat roof.

A few minutes later, he clambered down.

“Do you have a longer ladder?” he asked.

“Yes, but it wouldn’t fit in there,” David replied.

“That’s OK, I need it outside.”

Ignoring our puzzled expressions, Dad began pacing across the floor of the exhibition room.

“What are you doing I asked?”

“Counting. Damn, now I’ll have to start again.”

He continued pacing across the room, then turned and disappeared out of the door.

* * * * *

“Can you help hold the bottom?” Dad asked me as David propped a long aluminum ladder against the outside wall of Devon Mysteries.

“OK, but I wish you’d tell me what you’re doing,” I muttered.

I helped David hold the ladder steady as Dad climbed up with a roll of tools under one arm. When he got to the top, he unrolled the tools on a window ledge and selected a chisel.

He had paced out the distance from the end of the building before he positioned the ladder and now, satisfied that he was in the right place, he cut a hole in the fascia board immediately below the flat roof.

“What do you think he’s doing?” I asked David.

“I haven’t got a clue. You know what he’s like when he gets an idea in his head.”

I did. Years of experience had taught me not to question Dad when he was in the middle of something.

Finally, he rolled up his tools and came back down the ladder.

“Right,” he said calmly, “now all we need is a length of guttering.”

Back in Devon Mysteries, David and I helped him slide a length of plastic guttering up into the space between the ceiling and the flat roof. He manoeuvred it carefully between the metal wires supporting the ceiling tiles until it was exactly underneath the crack where the rain was seeping through. Then he pushed it forward until the far end stuck out through the hole he had made in the fascia board.

“There, now I just need to lift this end a little.”

He took a piece of wood from his pocket and jammed it under the guttering.

“Perfect.”

For a few moments, he listened to the gentle patter of drips, checking that all the rain was landing in the guttering and being safely channelled outside.

Finally, he climbed down the ladder and grinned at us.

“Luckily, it only needs to last for a few weeks. Just until we close in September. Like I said, there’s always another way.”

* * * * *

By the time the school holidays arrived, the grey skies had given way to a glorious English summer. Visitors queued at the gate every morning, and families filled the grounds and exhibitions. Each day followed the same pattern, and apart from being exhausted, we were all delighted by the way the year was progressing.

The wet early summer had given us problems indoors, but it had provided excellent growing conditions outside. The lawn had shot up at an alarming rate and I soon realised I would never cope clearing the weeds along the paths and under the trees by hand.

David and I brought up our concerns with the others, and they agreed that something had to change. David had already done his research and showed us an advert he had found for a second-hand ride-on mower. It would be an investment, but as we were having to pay a local farmer to cut the grass every couple of weeks, it should soon pay for itself.

There were no arguments. Within days, David’s new toy arrived, and I became the proud owner of an enormous, metal-bladed strimmer. It came complete with protective gloves, body harness, helmet and ear-defenders.

I loved it.

One evening, after settling Claire to sleep, I hurried outside and got myself kitted out.

Bob was preparing our evening meal, so I filled the strimmer with petrol, yanked the starter chord and smiled happily to myself as the engine roared to life.

The metal blade sliced effortlessly through the undergrowth and I felt like an explorer clearing a way through an undiscovered jungle.

At the far edge of the lawn, beneath an ancient oak and a magnificent tulip tree, lay an expanse of brambles. As I sliced through it, I found an ornate wrought-iron fence. I guessed it dated from the time the house had been built and was in surprisingly good condition.

Beyond the fence, the land dropped steeply to a lower level, and I found traces of what had once been a gravel path leading down through the woodland.

Closer to the house, an enormous clump of laurel bushes sprawled out across the lawn. Several of the branches were dead, and I spotted something square and angular hidden among them.

Tearing away a tangle of ivy, I revealed a massive concrete block standing on a square plinth. It was considerably taller than me, and while the front and back were flat and smooth, the sides jutted out in odd, irregular slopes.

I gazed at it for a long time, trying to work out what it was. There was no sign of walls nearby, just the one huge, grey block.

I couldn’t make sense of it.

Pulling off the last of the ivy, I noticed two circular holes that went right through the block and were lined with some kind of pipe.

The others were as confused as me.

“Was it supposed to hold something?” Phil asked. “Something that fitted through the two holes?”

“Like what?” David frowned.

“I’ve no idea. I was just wondering.”

“Maybe there was a lot more to it. Perhaps it doesn’t make sense because the rest is missing and this was just the foundation?” Mum suggested.

“But foundations go underneath something,” Bob pointed out, “not straight up in the air.”

“Whatever it is, it’s an eyesore. Can’t we just get rid of it?” I asked.

“We can try,” Dad said, “but it’s enormous and it seems to be one piece. Breaking it up would be a massive job.”

The others nodded in agreement.

“We can’t do anything about it now,” Dad went on. “Maybe we can try in the winter when we’re shut.”

“Could you grow something over it?” Mum suggested.

“I suppose so,” I agreed, “but it will take ages to cover it.”

David stepped back and considered the monstrosity from a distance.

“It’s a shame you cleared the ivy off it really, isn’t it?” he said at last.

* * * * *

Sometimes, late in the morning when we had finished the tea rush and before we started preparing lunches, I would walk over to the craft centre to make sure everything was running smoothly.

The centre had originally been built as classrooms and consisted of eight units around a central lawned courtyard. The workshops were spacious, with huge windows that gave them an airy feel, and each one had been decorated in an individual style.

There was nothing conventional about our craftspeople. In fact, they were an eclectic bunch.

Dougal, the woodcarver, was a tiny man with an enormous shock of grey hair. His small hands appeared too delicate for heavy work and yet he used chisels, axes and even a chainsaw with incredible precision. He was always happy to welcome visitors to his unit and encouraged them to watch him while he worked.

He enjoyed explaining the techniques he used and would stop what he was doing and give demonstrations of how tools were used if someone showed a particular interest.

Opposite him, across the courtyard, were the glass engravers. Elliott was tall, pale and quiet while Marion, his wife, was short, round and bubbly with olive skin, jet black hair and a permanent smile.

They were both accomplished artists and could engrave the most detailed images of animals, flowers or even portraits onto any object made of glass.

In addition, we had a toy maker who produced traditional wooden toys, a knitwear designer who created amazing jumpers, dresses and coats, and a pair of picture-framers who specialised in bespoke frames that often out-shone the pictures they surrounded.

But although the craftspeople were diverse, the one thing they all had in common was their friendly manner. The only exception was Tom Stevens, the potter.

Tom was an excellent craftsman, but he was terrible at dealing with the public. I don’t think he meant to be rude, but he often was.

I once heard him tell a family, “If you’re not going to buy anything, please leave. I can’t concentrate with you standing there watching me.”

I was horrified.

“Tom, people are far more likely to buy something if you make them feel welcome,” I said as the family shuffled out of the room.

He looked at me in surprise.

“I do make them welcome,” he protested, “but that family had been standing there for ages. I don’t complain normally, but it’s disconcerting when they just stare at me. What more do they want? I’m not going to make them tea and biscuits, am I?”

“Maybe you could talk to them?” I suggested.

“Why? They come to see the crafts, don’t they? Not to gossip.”

It felt hypocritical of me to say he should spend more time talking to people, but I persisted.

“Perhaps they’d like to know more about you. After all, they only come in here because they’re interested in you.”

Tom’s face darkened.

“I don’t want them to be interested in me. I want them to be interested in my pots.”

I tried again.

“Then maybe you could tell them how you make them? About your processes? All the steps that go into each…”

“Impossible!” Tom looked at me as though I was mad. “I don’t have time for that sort of thing. I’d get no work done at all.”

* * * * *

I was emptying the dishwasher in the kitchen when Mum phoned me from the ticket box. I could tell at once that somebody was with her. She was using her formal voice and sounded like a newsreader.

“There is a visitor to see you,” she announced. “It is Mr North from Torrington Bank. Is it convenient for me to send him up to the house?”

“Yes, of course. I’ll come and meet him.”

As I dried my hands on a towel, I wondered what Mum would have said if I’d told her it wasn’t convenient. She could be unpredictable at times and it was easy to imagine her telling Mr North that he should have phoned to make an appointment before coming.

It occurred to me that if I had been in the craft block and hadn’t had my walkie-talkie with me, she would probably have sent him away. I winced. Mr North was not like any of the other bankers I had met. We had spoken to many of them while trying to raise the finance to start Silverlands, but it had only been Mr North who had given us a chance.

We owed him a huge debt, but I knew Mum would have seen it differently. She didn’t believe in banks, but then, she didn’t believe in politicians, or solicitors, or doctors either. I paused for a moment as I realised my mother didn’t trust anyone in a position of authority. In fact, she didn’t trust anyone except Dad and David and me.

The realisation came as a shock, but I knew it was true and suddenly I understood why she struggled to accept Bob. It wasn’t about him. It was about her. It wouldn’t have mattered who I had wanted to marry. She would not have accepted him.

I had never brought a boyfriend home to meet my parents. Not once. It had not been a conscious decision, but I had always avoided it. Now I wondered why. I had not worried about introducing them to Dad. I knew he would have teased me, but he would have been his usual, cheerful self. Mum would have been a different matter. She would…

A deep voice in the servery cut through my reflections and I jumped guiltily. How could I have let my thoughts run away with me?

I hurried through and held out my hand.

“Good to see you, Mr North. I hope you’re keeping well?”

“Yes, thank you. I didn’t want to disturb you, but I was passing and I thought you might have a few minutes to tell me how things are going.”

He smiled down at me and his stiff, upright bearing made me wonder if he had been in the army.

“Absolutely, but would you like a cup of tea, first?”

“Maybe later. I was hoping you could show me around and give me an update on your progress.”

Martha was behind the counter and nodded that she could manage on her own.

“I’d love to.”

It was mid-morning and Bob was about to introduce the morning show. We had laid out a circle of hay bales on the main lawn and families sat around waiting expectantly.

Mr North followed me across and watched as Bob stepped forward, resplendent in his red coat and top hat. He ran through his patter and the audience cheered.

“And now, are you ready to be amazed?”

The audience shouted back, but Bob held his hand to his ear.

“What was that? I can’t hear you? Are you ready?”

“Yes!” the audience roared.

I glanced at Mr North and was pleased to see he was smiling.

“Then let me introduce the greatest juggler this side of the river Teign! The amazing, the talented, the one and only Mighty Max!”

The audience cheered as Max appeared from behind the laurel bushes perched on a six-foot unicycle juggling a rainbow of brightly coloured hoops. Bob stepped back, and I waved to catch his attention.

“Hello, there!”

Bob held out his hand and greeted Mr North with a wide smile. “Good to see you. You’ve picked an excellent day to visit. We’ve got a lovely crowd in.”

“Yes, I can see that.”

I had expected Mr North to move on, but he stayed and watched the show with interest and clapped as loudly as the children.

I showed him through the attractions, pointing out the most popular displays, and introduced him to David in the gift shop, Phil in the Animal Meadow, and the craftspeople in their workshops. Finally, we ended up back at the tearooms.

“I won’t keep you much longer,” he said as we sat down at a corner table.

“It seems to me that everything is going well. It’s unfortunate that the poor weather has caused you problems, but hopefully the rest of the summer will be better. It’s very satisfying to see you at this point, but…”

He broke off as Martha arrived with a tray of tea and a plate of flapjacks. I poured the tea into the cups and waited for him to continue, but he was silent.

I was about to comment on how much people had been spending in the gift shop when Mr North cleared his throat.

“There is one thing I want to bring up with you.”

I looked across at him, and his pale blue eyes met mine.

“When you and your mother first approached me about financing this project, I explained that I have great confidence in family-run companies. In my experience, they have much greater resilience than a group of people that have been brought together purely by a business opportunity.”

I nodded earnestly.

“But there is one other thing I would like you to consider. Your family are very talented and diverse. They all bring unique abilities to the business. In some ways, they are like the members of a crew. If you want to sail a ship across an ocean, you need lots of different crew members, engineers, officers, caterers.”

He paused and sipped his tea before continuing.

“The ship won’t run smoothly without all the crew members but, however well each one does his job, the journey will end in disaster if someone isn’t constantly on watch checking the ship is navigating properly. It’s exactly the same with a business. It’s easy to concentrate on the day-to-day activities, but someone needs to keep a long-term view, decide where you want the business to be in five years’ time and work out how to get there.”

I nodded again and waited for him to go on.

“In my opinion, in your family, that person is you. You’re the one that must keep the ship on course. Make sure that everyone is pulling together in the same direction.”

He was looking at me, expecting me to agree with him.

“But our family isn’t like that,” I said. “We make all our decisions together. All six of us have an equal vote in everything.”

“Democracy is wonderful,” he said quietly, “but please consider what I’ve said. Now, I think I had better get back to the office.”

* * * * *

As the summer rolled on through weeks of sunshine, a steady stream of visitors kept us busy. Our daily routine became second nature, and in the evenings, Bob, Claire and I ate our meal on the tea lawn while the dogs charged around us.

Life was wonderful.

Finally, when September arrived, and the schools reopened, the number of visitors dropped and the queues in the tearooms shrank.

“Do you remember the last time we had a day off?” David asked one afternoon as we all gathered in the tearooms after closing.

I laughed.

“It was before we saw this place for the first time, so that would be about eighteen months ago, wouldn’t it?”

“We did take Christmas Day off,” Mum corrected me.

I laughed again.

“Yes, you’re right. I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to exaggerate.”

“Still, it will be nice when we shut,” David said. “It’s only a few weeks now until the end of September, then we can close the doors until next Easter.”

“I am looking forward to having the place to ourselves again,” I admitted.

Bob stretched out his legs and leaned back in his chair.

“I saw a report on the news last night. Apparently, the value of an average house has gone up by twenty-seven percent in the last twelve months. That’s incredible, isn’t it? It made me think about this place. Last year, it was a derelict wreck with a demolition order hanging over it, and now it’s renovated and open for business. It would be interesting to know what value the estate agents would put on it.”

“Yes, it would,” I agreed. “Whichever way you look at it, the value must have increased hugely.”

Mum nodded.

“And property prices never go down, do they?”

“But it’s not true to say it’s all renovated,” Dad chimed in. “We’ve still got a lot to do. Apart from the roof on Devon Mysteries, there are still two craft units we haven’t touched. And don’t forget the dormitories at the back, let alone the swimming pool and the sports hall.”

“Did you have to remind us of all that?” David groaned. “I was just thinking how well we’re doing.”

“We are doing well,” Dad agreed, “but I don’t want you thinking we can take a lot of time off just because we’re closing to the public.”

“Well, I think we should,” Mum cut across him. “We deserve it. We close on the last day of September and, after that, I think we should all take a week off.”

Dad looked amazed as the rest of us cheered.