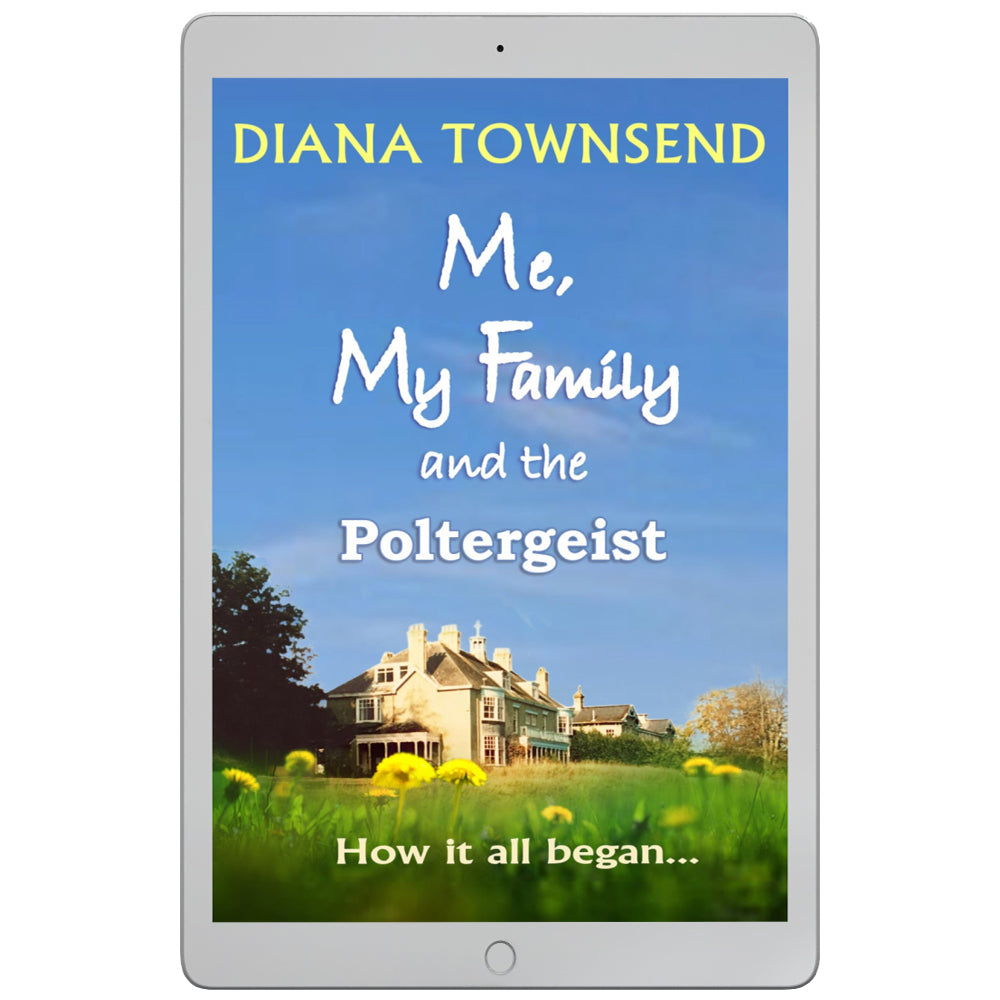

Me, My Family and the Poltergeist (EBOOK)

Me, My Family and the Poltergeist (EBOOK)

Diana Townsend

📚 This ebook is available on Amazon Kindle Unlimited!

EBOOK. THE FIRST BOOK IN A SERIES OF THREE MEMOIRS.

Diana Townsend realizes at a young age that her family are different from other people. Her mother is an author and her father is a circus owner who has been forced by ill-health to close his beloved show.

Growing up, Diana and her brother, David, help their father build a remarkable animated model of his show, Silvers Circus, which they exhibit around the country.

Soon the family dream of opening their own tourist attraction.

Hosting a derelict school is up for sale, they make an impulsive decision to sell their home, pool their savings, and risk everything on making their dream a reality.

Not believing in ghosts, Diana is amused to hear local people claim the old building is haunted. However, once renovations begin, her feelings change.

As the opening day approaches and unexpected problems threaten the family with ruin, Diana becomes convinced they are sharing their home with a ghost. But is she right? And will the rest of the family believe her?

Share

Read a Sample

Read a Sample

INTRODUCTION

My daughter Lucy was visiting with her partner when she asked the question.

“Mum, can you tell Dave about the White Lady?”

“Me?” I stared at her. “Why me? You were the one who spoke to her.”

“Mum!” Lucy retorted indignantly. “I was four when we left Silverlands. I hardly remember anything about it.”

“Seriously?”

I felt a strange mixture of surprise and sadness. Silly, really. I should have realised that, to a young woman, something that happened twenty years ago might as well have taken place in the Middle Ages. To her, it was a lifetime ago, but to me, those days still seemed as clear as yesterday.

And if Lucy had forgotten, perhaps Claire and Michael had forgotten too.

It was then that I decided to write an account of what had occurred as a permanent record for my daughters, Claire and Lucy, and for my nephew, Michael.

After all, it is not every family that gets to share their home with a poltergeist.

CHAPTER 1

As a teenager, I didn’t believe in ghosts.

I loved reading ghost stories, of course, and watching horror films, but if anyone had tried to tell me that ghosts, ghouls and things-that-go-bump-in-the-night really existed, I would have laughed at them.

Everyone knew ghosts were nothing more than superstitious nonsense, didn’t they?

Back then, it had all seemed so simple.

* * * * *

But first, I had better explain about myself and my family.

As a child, I always knew that my parents were different. Not different in a bad way, but different. A little eccentric, perhaps. A little bit more creative than most. It didn’t bother me, though, because I loved them and I was proud of them.

Mum and Dad were older than any of my friends’ parents, as they had both been in their forties when I was born and had led full and unusual lives before coming to settle in England.

My father had been born in Sydney, a fourth-generation Australian, and had trained in the family business to become a tent-maker. Later, he and his brother had built a circus tent of their own and had taken to the road with their show, Silvers Circus.

Mum, on the other hand, had been born in London. Her family emigrated to Australia when she was eleven, so she grew up in Perth but returned to England, aged sixteen, determined to become a writer. She worked in Fleet Street during the Blitz. Then, when she was in her thirties, she went back to Australia to find material to use in her books.

While travelling through the Nullarbor Plain, her car had broken down, and she had been rescued by my father, who was crossing the country with his circus.

After a whirlwind romance, they married and, a year later, my brother, David, was born.

Mum told me once that the months after David’s birth were the happiest she ever knew. She had found the love of her life and a bright future lay ahead of them.

Sadly, her idyll was short-lived.

Out of the blue, Dad was struck down by a mystery illness. The doctors could not agree what the problem was, only that he had contracted a viral infection of the brain, probably a form of meningitis.

At first, it seemed he would not survive, but when, with customary stubbornness, he refused to die, my mother was warned he would be left with brain damage and would never be able to work again.

With a baby and an invalid husband to care for, Mum decided to return home to England. As a child, she had lived in the East End of London but, rather than return to the bustle of the capital, she felt the slower pace of life in Devon might help Dad’s recovery and so the family settled in Exeter.

Against all the doctors’ predictions, Dad’s health slowly returned and, as he grew stronger, he began to think of ways to earn a living.

There were few opportunities for circus owners in Devon at that time, so he decided instead to set up a business as a silk-screen printer. Neither he nor Mum knew much about printing, but Dad got a book from the local library and built the printing tables, screens and drying racks himself.

A couple of years later, I was born and for the next twenty years, the printing business supported our family.

Although he always worked long hours, Dad never fully recovered from the effects of his illness. He suffered from headaches, sometimes lasting for days, which were so severe they left him partially paralysed and unable to speak. On more than one occasion, he collapsed over the printing table. Despite these setbacks, Dad would never give in and, as soon as his head cleared, and usually sooner than my mother wanted, he would return to work.

My father could never, in any way, be described as average. He was a big bear of a man with a warm heart and an infectious laugh who could find the humour in even the most difficult situations. Naturally quiet, he was one of life’s observers, which meant that few people realised he had an unusual ambition.

As a teenager, he had spent his days training in his father’s tent-making factory, designing and making tents for the biggest circuses in Australia, but, in his spare time, he had built a tent of his own. It was a scale model, perfect in every detail, a miniature replica of a circus big top, and he brought it with him to England, locked away in a trunk, in the hope that one day he would be able to finish it.

* * * * *

Yes, my parents were different, and in some ways, I think I was different, too.

I found it hard to fit in at school because I never seemed to have anything in common with the other children. I wanted to be friends with them, but I had no idea how to do it.

My classmates seemed to know instinctively how to start conversations or join in with games, but I never learned their secret and always ended up on my own watching everything from a distance.

It wasn’t that I didn’t like the other children. It was just that they seemed strange to me. They enjoyed things I didn’t understand, like music and sport.

Many of our lessons involved songs, and the other children seemed genuinely to enjoy them. They would shriek with delight whenever a teacher pulled open the instrument store, but the sight of a box filled with tambourines and bongo drums made my heart sink.

I worried there must be something wrong with me and wondered if I was really the only person in the world who didn’t like music.

I can still remember how excited I felt on my first day at Stoke Hill Junior School. I was seven years old and was already a confident reader. My favourite subject was maths and Mum had helped me learn my multiplication tables by heart, so I knew I was ready to start my formal education.

Stoke Hill was considered a progressive school. The newly completed buildings were bright and welcoming and stood high on a hill, surrounded by tarmac playgrounds and grass sports fields. The corridors and classrooms were painted in cheerful pastel colours, and huge windows allowed daylight to flood into every corner.

It was one of the first schools in Devon to try out a new form of child-led learning where pupils were allowed to work at their own rate instead of having all the class follow the same lesson. At the time, it was considered a radical approach to education, and we had regular visits from assessors to see how the new system was progressing.

Each morning our teacher handed out work cards to the class which were supposed to keep us busy until playtime. Some of the children became bored quite quickly and were allowed to change to activity-based tasks such as weighing sand with scales or making plasticine sculptures, but I was perfectly happy sitting at a table completing my work as neatly as I could. As soon as I finished a card, I would return it to the teacher and ask for another one.

It wasn’t long before I finished all the cards in the box and the teacher told me I would have to wait for the others to catch up with me before we could all move on to a new set.

The next day I asked if I could start the new work cards yet, but my teacher told me I would have to wait. She suggested I read a book from the pile in the corner, but I explained that I had already read them all.

I asked again the next day, and the next day, and the next, until, finally, my teacher suggested I bring a book from home to read. She seemed surprised when I arrived with a copy of Collins Guide to European Butterflies and a dictionary in case there were any words I didn’t understand.

I don’t think she expected me to enjoy the book, but I loved it and read it from cover to cover several times, trying hard to memorise all the information.

By then, I had come to the conclusion that my classmates were not very bright. They didn’t seem interested in lessons at all and only wanted to run around the playground screaming.

For me, playtime was the worst part of the day. I disliked it intensely. It was noisy, disorganised, and frightening. Worst of all, when I begged the teachers to let me stay inside and read, they told me that standing on my own, shivering, in the playground while they sat in a warm staff room drinking coffee, was good for me.

I began to think my teachers weren’t very bright, either.

* * * * *

My brother, David, is seven years older than me and we were always inseparable. When Dad was ill and Mum was preoccupied looking after him, it was David who kept me busy.

He would push me around the garden in his go-kart, make tents out of blankets, or teach me how to wage war with his toy soldiers.

On the weekend, David and his friends were allowed to go to Saturday Morning Picture Club at the local cinema where they enjoyed cartoons, children’s films and serials like The Perils of Pauline, where each episode ended with the heroine tied to a railway track or about to fall off a cliff.

Every Saturday, David begged to be allowed to take his little sister to the cinema with him, and I screamed at being left behind, until eventually, I became the youngest member of the club and was allowed to spend three hours a week staring at the screen with the big boys.

During the week, particularly during the holidays, David and I would act out our favourite scenes and, as I got older, we began to make up our own stories. We wanted to shoot films ourselves and dreamed of travelling the world and making movies in wonderful, exotic locations.

* * * * *

For a special treat, my parents took me to see Disney’s Snow White at the cinema. I hated it, mainly because the wicked stepmother reminded me of my grandmother.

Of course, Granny was not tall or beautiful or magical. but she was exceptionally vain and jealous and treated my mother in much the same way that the wicked stepmother treated Snow White.

When the wicked stepmother transformed herself into an old lady and set out with her poisoned apple, I screamed so much that my mother had to take me out of the cinema.

One of my earliest memories is of hiding under a sofa while my grandmother screamed and shouted. I can remember burying my face in the carpet and shaking. I was absolutely terrified of her and, as I grew older, my fear turned into a deep loathing.

As a child, I didn’t understand why Granny was so horrible to everyone. Even when she was trying to be nice, there was a coldness about her that drained the happiness from a room the moment she walked into it.

As an adult, I came to understand that she was a deeply unhappy woman who had been shaped by her life experiences. Intelligent and talented, she had been born into extreme poverty in the East End of London. Her mother had refused to let her go to school and had kept her at home to help with the housework and to look after her younger siblings.

When the school inspector arrived on the doorstep, Granny had been made to hide in a cupboard while her mother pretended that she had been taken ill with scarlet fever and had been sent to live with relatives in Brighton.

As she grew up, Granny had rebelled and found herself married with two young children while still in her teens.

She was clever and articulate but, barely able to read or write and with a young family to support, Granny spent her life scrubbing other people’s floors or washing up in pubs and became bitter and resentful.

She took pride in the fact that she never made friends, but had a long list of enemies.

I think she was jealous of my mother because she saw in her a vision of how her life could have been, if only she had had the same opportunities. As she grew older, Granny became manipulative, violent, and increasingly insensitive to other people’s feelings.

I didn’t know until many years later, but when my mother was six months pregnant with me, my grandmother tried to push her down a flight of stairs. Fortunately, Mum had managed to catch hold of the bannister, and neither she nor I were hurt.

Granny insisted it had been an accident but my mother didn’t believe her and, after that, my father had to make sure the two women were never left alone in the house together.

Dad told me once that he had begged Mum to walk out, but she had refused to leave, fearing that if she went, Granny would have been unable to cope on her own and would have ended up getting herself arrested.

It was probably the stress of living with Granny that led to my mother having a nervous breakdown when I was born.

My brother often teased me that I was so ugly that Mum took one look at me and collapsed.

Dad simply told me that Mummy had been very tired when I arrived and the doctors had put us into special rooms so that she could have plenty of rest.

When I grew up, Mum explained that, as she had recently arrived from Australia, her doctors had assumed that she had some strange tropical disease and, immediately after my birth, both she and I had been put into separate rooms in the isolation unit. For the first week of my life, she had not been allowed to touch me as I lay in a sterile box tended only by nurses wearing masks and thick rubber gloves.

Perhaps that was where I learned to enjoy being on my own.

* * * * *

My brother is dyslexic. Or rather, he is dyslexic now. When he was a child, he was just stupid and lazy, at least, that was what his teachers called him.

Back then, no one had heard of dyslexia, but Mum was convinced there must be a reason for David’s inability to read or write.

For years, she wrote to every educational expert she could find and sent letters to newspapers and universities. Eventually, she discovered a professor who was researching “wordblindness” and, as a result, David was the first child in Devon to be officially diagnosed as dyslexic.

By then, he was fifteen and his teachers refused to believe that such a condition existed.

He left school with no formal qualifications, having endured years of being told he was retarded, when in reality, he was intelligent, talented and creative.

My mother never believed there was anything wrong with David. She knew he had gifts and abilities and devoted her life to helping him learn.

Every afternoon, as soon as he returned from school, she would make him go through the same list of spellings day after day after day, in the hope that they would finally stick in his memory.

I always enjoyed lessons and one day, when I was about six and David was thirteen, I asked if I could join in.

Mum gave me a piece of paper and, as she read out the words, I wrote them down in large, round letters.

Then, as Mum corrected David’s work, I carefully ticked the words off my list.

“Look,” I squealed, “I got them all right!”

I had expected them to be pleased.

Instead, David leaped to his feet and tore his paper to shreds.

“I’m not doing this anymore!” he shouted. “It’s useless. I’m rubbish, aren’t I? I’m never going to be any good at anything!”

The door slammed as he ran out of the room and I realised, for the first time, that doing well in tests doesn’t make you popular.

* * * * *

In the sixties, eating disorders had not been invented.

The memories of wartime rationing were still fresh in people’s memories and it was considered a sin to waste food.

Milk arrived on our doorstep each day in glass bottles. The tops were sealed by shiny foil tops that glistened in the morning sunlight and proved irresistible to blue tits.

Every morning, as soon as she came downstairs, Mum would hurry to the front door and carry the milk bottles through to the kitchen. Usually the foil bottle tops would have dents where the blue tits had been pecking at them with their sharp black beaks, and occasionally there would be a tear where a bird had broken through to the creamy milk beneath.

Often, the bottles were smeared with bird droppings and Mum always rinsed them carefully under the tap before putting them in the fridge.

As I watched her, I worried that some of the droppings might have got into the milk. What if the birds had poo on their claws, as they hopped around on the foil?

Soon my mind associated milk with bird droppings. I didn’t want to upset Mum by explaining, so I stopped drinking milk. Every time she put a glass in front of me, I sat staring at it, sometimes for hours, as my mother encouraged or scolded me.

I thought if I waited for long enough, Mum would give in and take the milk away, but she never did.

Day after day, she would plonk a full glass in front of me and the battle of wills would begin. Sometimes I cried, sometimes I begged her to take it away, but mainly I just sat silently staring at the glass, trying to spot traces of bird poo floating in the whiteness.

It was not long before I realised food might contain unpleasant substances too. I studied the Weetabix that was waiting for me each morning and decided some of the smooth flakes of wheat looked suspiciously like insect wings. I told Mum I didn’t feel hungry and I wouldn’t need any breakfast in the future.

I stopped drinking tea because, in the days before tea bags, the tea leaves looked like drowned flies.

Fruit juice was rejected because it had “bits” in it and soon I would only drink water.

I refused to eat brown bread and became suspicious of anything that might have dirt hidden in it. I even spread mashed potato across my plate to check it was untainted before I eating it.

I sensed that my behaviour was upsetting my mother. She sat by me for hours at mealtimes, insisting I couldn’t leave the table until I had eaten something, but she never lost her temper or shouted at me.

Granny wasn’t so patient. One night, when Dad was ill and Mum was upstairs looking after him, I can remember her plopping a bowl of rice pudding down in front of me and insisting that I eat it.

When I refused, she took a spoon and tried to force the rice pudding into my mouth. I spat it out, but she simply scraped the rice up from the tablecloth and shovelled it back into my mouth.

I tried to protest, but she stood behind me, the spoon clamped in her right hand, while her left arm wrapped across my chest, pinning my arms to my sides.

I wriggled and squirmed and choked as she forced the sweet, creamy pudding into my mouth and felt myself retching as some of it slid down my throat.

Each time I swallowed, I tried to call out, but my protests were choked by another spoonful of rice.

Tears of indignation filled my eyes and frustration churned my stomach until, finally, with a horrible rasping sound, I vomited with such force that the returning rice pudding hit the bowl and splattered up all over Granny.

She gasped in shock and I seized the chance to wriggle free and race upstairs to the sanctuary of my bedroom.

I can remember lying on my bed crying as my grandmother’s voice echoed up from downstairs.

After that, mealtimes became a misery.

I didn’t want to upset my mother because she was always kind and patient with me, but I had absolutely no appetite. I never felt hungry, and the thought of eating tied my stomach in knots.

Dad tried to help by challenging me to races. Who could eat the most peas? Or finish their potato first? It didn’t work.

At school, I was made to sit at the table, staring at an untouched plate of food, long after the other children had left. When the dinner ladies wanted to clean the dining hall, I would be made to sit in the corridor outside the headmaster’s office until the bell rang for afternoon lessons. This didn’t worry me too much as it meant I avoided playtime, but I just wished everyone would leave me alone.

It was only when my mother took me to see the doctor that I realised things were getting out of hand.

The doctor weighed and measured me, then made me strip down to my knickers before poking my stomach and tutting at my protruding ribs and hipbones.

“Why won’t you eat the meals your Mummy cooks for you?” he asked.

I knew he wouldn’t understand, so I sat silently staring down at my shoes.

He repeated the question, but I didn’t have an answer for him.

“There is nothing wrong with you, is there?” he said at last. “You’re just being silly.”

I looked up, but he was frowning, and I let my eyes drop back to my shoes.

“Your mummy and daddy are very worried about you. You don’t weigh nearly as much as you should do at your age.”

I pressed my back against the chair and began to fidget nervously.

“There is only one answer.” The doctor’s voice was loud and resolute. “If you don’t start eating properly, I will have to send some nurses to your house to take you away and put you in a special hospital. You won’t be allowed to go home and you won’t see your mummy and daddy again until you learn to do as you’re told and eat what you’re given. Do you understand?”

Fear gripped me and I blinked back tears as I nodded.

“Good. Remember, I have lots of seriously ill patients to look after and I don’t want to waste my time talking to little girls who are being fussy about their food.”

As I pulled on my coat, he turned to my mother.

“I think that should do the trick.”

“Thank you, doctor,” she replied gratefully.

As soon as we were out of the surgery, I burst into tears.

“You won’t let the nurses take me away, will you?” I begged.

That night I tried hard to eat my evening meal, but the food seemed to grow in my mouth until I felt like a hamster with bulging cheek pouches. My throat had constricted to a tiny tube and the more I tried to swallow, the more I felt myself beginning to retch.

“She’s playing up again,” my grandmother said coldly. “Remember, dear, there are plenty of children in India that would be grateful for that food.”

I wanted to tell her that the children in India were welcome to all my food, but I was afraid that if I opened my mouth, I would be sick across the table again.

It was Dad who took pity on me.

“This isn’t doing any good,” he said. “She ought to be in bed by now.”

He watched as I cleaned my teeth and pulled on my pyjamas, then he tucked me into bed with his big hands and sat down beside me.

“Mummy’s really worried about you.”

“I know.”

“Why won’t you eat your food? She tries very hard to make nice things.”

“I know,” I repeated.

“Then what’s the problem?”

He stroked my hair gently, and I knew he really wanted to understand.

“She mixes it all up,” I said at last. “She puts it on the plate so it’s all touching each other. I would eat some of it, like the mashed potatoes, but it’s all mixed up with the cabbage.”

“What’s wrong with the cabbage?”

“It’s not the cabbage…” I began hesitantly.

“Then what is it?”

I sniffed.

“It’s the footprints.”

“What footprints?”

I was silent for a long time and Dad kept stroking my hair as he waited.

“It’s the things that live on the cabbage,” I said at last. “It’s the greenflies and the caterpillars. They leave footprints.”

For a moment, he gazed at me, then his face broke into a grin.

“Are you telling me you won’t eat your cabbage because you think greenflies have left footprints on it?”

He wrapped his arms around me, and I felt him shake with laughter.

“It’s not funny,” I protested. “They might have pooed on it too.”

“They probably did,” he agreed. “Greenflies do that sort of thing.”

“Don’t laugh at me!” I pounded his chest with my fists but, deep inside me, the tension eased.

“But you’re the one who says funny things!”

“It’s not funny, it’s serious,” I protested, but Dad tickled me.

“You’re laughing!” he teased. “You mustn’t laugh. This is serious.”

“I know. It is serious,” I insisted, but his laughter was infectious.

I wriggled away from him, but he went on tickling me until I shrieked with laughter. Finally, I leaned my head against his shoulder and knew I was safe.

“Please don’t tell Mum about the cabbage. She wouldn’t understand.”

“No, I don’t think she would,” Dad agreed. “How about I ask her to keep the different foods separate on your plate? That way, you can eat the things that don’t have footprints on them.”

“Yes, please.” I nodded. “And can I not have any gravy? It makes everything look like mud.”

“Okay,” he agreed. “I’ll ask her.”

He hugged me tightly, and I knew then he would never let the nurses take me away.

“I love you, Dad,” I whispered.

* * * * *

David was always mad about guns.

He had a huge collection of toy pistols and cowboy rifles and, as a toddler, I would trail behind him, pointing my finger and shouting “Bang!”

When David became a teenager, Dad bought him an air rifle, and I begged to be allowed to have a turn shooting at the row of battered Coke cans at the bottom of the garden.

The air rifle was much too heavy for me but I soon found that if I leaned the end of the barrel on the back of the garden bench and used two fingers to pull the trigger, I could send the cans flying as well as anyone else.

After that, whenever David had his friends around for a shooting competition, I would pester them to let me join in. They were reluctant at first, but eventually they gave in, and over the following years, I spent many happy hours firing lead pellets along the length of the garden.

* * * * *

I always found it hard to understand my mother’s relationship with Granny.

“Do you really love her?” I asked one day as she scrubbed the collars of Dad’s shirts with a bar of soap before putting them into the washing machine.

“Of course, I do,” she replied. “She’s my mummy.”

“But that’s not a reason.”

“Yes, it is,” Mum said firmly. “It’s a daughter’s duty to love her mother.”

“I’ll bet it was Granny who told you that.”

Mum stopped scrubbing and looked at me in surprise.

“And why doesn’t it work the other way around?” I went on. “What about a mother’s duty to be loveable? I mean, I don’t love you just because you’re my mother. I love you because you’re nice to me.”

“So, if I stopped being nice to you, would you stop loving me?” she asked.

“Of course, I would,” I said bluntly, “and I’m not going to love Granny just because she’s my grandmother. I hate her because she’s horrible to everyone. Nobody has the right to shout at people like she does.”

Mum blinked quickly as she started scrubbing again.

“That’s enough,” she said. “I think it’s time you went and played in the garden.”

* * * * *

I knew Granny and Granddad had lived with us when I was a baby and I wondered why they had moved into a little flat of their own. When I asked David what had happened, he seemed reluctant to tell me but, after a little nagging, he gave in.

“There was a fight,” he said. “You would have been about two at the time. It was worse than usual and Granny ended up smashing everything. When Dad tried to stop her, she bit his hand so hard he had to go to hospital and have seventeen stitches put in it.”

“That must have hurt.”

“Yes, I expect it did,” he agreed. “The doctors came and saw Granny and said they wanted to put her into a special hospital, but Granddad wouldn’t sign the papers.”

“Why not?”

“Because she would only have been there for a while. Granddad said if they did that, Granny would kill him when she came out, so he wouldn’t sign. That’s when Dad said we had to leave and move here.”

“Good,” I said. “I’m glad we left, but I wish we had taken Granddad with us.”

* * * * *

By the time I started junior school, Mum had made peace with Granny. She and Granddad visited us every week, and I often spent time with them during the holidays.

As the first day of term approached, Granny gave me some advice.

“Remember, dear,” she said sternly, “I’m sure you will find it very frightening when you start at the big school, but there’s one thing you must remember.”

I looked up at her and she considered me for a moment before she went on.

“Whatever happens, you must hold your head up high and pretend you’re as good as everyone else. That’s what I do.”

It seemed to make sense at the time and I think, for once, she was genuinely trying to be helpful, but now, as I look back, I can see the flaw in her logic and understand how much it said about her life.

* * * * *

Despite being a happy child, I was always fascinated by death.

When I was seven, my Uncle George was killed in a car crash. I can remember being woken in the middle of the night by the noise of a police officer banging on the front door to tell my mother that her brother was in critical condition in hospital.

The strange thing was that Mum and George had been estranged for years but, in the weeks before his death, she had been haunted by premonitions that something was going to happen to him. She had even taken to reading the obituaries in the local paper to check for his name.

After his funeral, I found myself thinking a lot about what it would be like to die.

Mum and Dad wouldn’t answer my questions, and I wasn’t convinced that David knew any more about the subject than I did.

I tried asking Granny, but she only burst into tears and told me I was an unfeeling brat.

I didn’t understand why she was so upset that Uncle George had gone to heaven. The description I had heard from my mother made heaven sound wonderful. No school, no food, no arguments. Nothing to do but play all day and talk to Jesus.

Yes, heaven sounded wonderful and I couldn’t understand why everyone didn’t want to go there straight away. Soon, I began wondering how people actually got to heaven.

You had to die, of course, but I didn’t know exactly what dying meant. I had heard about people passing over, or going through the gateway, or slipping away from this world, but none of those phrases made sense to me.

I knew people could die by being strangled, or stabbed, or drowned, or burned, or run over by a car, but I longed to know how it felt to go through that ultimate transition and arrive in paradise. I knew there would be pain involved, but that didn’t discourage me at all.

In my mind, dying seemed very exciting.

Eventually, I decided that if no one would explain how death worked, I would try to find out for myself. It didn’t make any sense to me to spend years coping with school, eating and having to talk to people, if heaven was really so much better.

A few days later, my mother found me laying in the road near our house waiting for a car to catapult me to heaven. Luckily, I had chosen a quiet backstreet and all the drivers had managed to avoid me.

With hindsight, it seems strange that no one had stopped to find out why a small girl was lying in the middle of the road. Apparently, one of my classmates’ parents had recognised me and summoned my mother.

I had never seen my mother cry before.

It had not occurred to me she might be upset by my plan and I tried to explain that I had not meant to make her sad, but she just kept weeping and asking me to promise never to do such a thing again.

Dad arrived soon afterwards and his face was so grey that I knew he was about to slide into another headache. I promised I would never try to get myself run over again and felt genuinely sorry for the upset I had caused.

But it did not change the way I felt about death. It still seemed like a great adventure, and I couldn’t wait to experience it. However, to avoid upsetting anyone, I decided to delay my next attempt until both my parents were safe in heaven, waiting for me.

* * * * *

I always felt sorry for Granddad. He was a tiny man with worried eyes and a shiny bald head, and I knew he was as frightened of Granny as I was. Sometimes he would take me shopping with him and we would have to walk from one end of Exeter to the other to find shops that would serve him. Most of the butchers and greengrocers had banned him because of the number of times Granny had complained about what he had bought and had made him take things back.

When Uncle George died, Granny was heartbroken, but her reaction, three years later, when Granddad died, was very different.

As usual, Granddad had been sent out with a long shopping list, but he had suffered a heart attack in the street and had been taken to hospital in an ambulance. By the time Granny got there, he was already dead.

Shortly afterwards, Granny arrived on our doorstep and, as Mum opened the door, her first words were, “Your father’s gone and died and he hasn’t even signed his pension book. His pension’s due tomorrow, so that means I’m going to lose a week’s money. He always was an inconsiderate man.”

I begged to be allowed to go to Granddad’s funeral, but Mum wouldn’t hear of it. She said that my headmaster wouldn’t give permission for me to miss school, but I am sure that she never even asked him. I think she was afraid I would start thinking about death again.

* * * * *

As soon as the funeral was over, Granny packed all Granddad’s clothes into bags and arranged for them to be taken to the tip. Then she began visiting second-hand shops and selling her jewellery and knick-knacks.

“Don’t you want them anymore?” I asked innocently.

“Not where I’m going,” she answered.

“Where’s that?”

“A long way away where no one will have to worry about me.”

I knew better than to pester Granny when she was in a mood, so I waited until later and repeated her words to David.

“What do you think she meant?”

“No idea.” He wrinkled his nose. “Maybe she’s going to kill herself.”

“I hope not.” I said earnestly.

“Really?” David looked at me in surprise. “I thought you hated her.”

“I do,” I agreed, “but it wouldn’t be fair on Granddad. Not yet. He deserves some time in heaven on his own.”

* * * * *

A few weeks later, I returned from school to find Mum crying and Dad sitting with his head in his hands.

“What’s wrong?” I asked in alarm.

“It’s all right.” Dad reassured me. “It’s your grandmother. She’s going on a trip and Mum’s a bit worried about her.”

“What sort of a trip?” I asked.

“She’s going back to Australia,” Mum blurted. “She says she’s going to find herself a new husband.”

“Really? That’s great!”

“No, it isn’t!” Mum burst into a new flood of tears. “She’s going to get herself into all sorts of trouble, and I won’t be there to get her out of it.”

“We can’t stop her,” Dad said tiredly. “She’s sane. At least the doctors say she is, and she’s managed to raise enough money for the journey. Her sisters will have to look after her once she gets there.”

He put his arm around Mum’s shoulder and kissed her hair.

“Maybe it will all work out for the best.”

“No.” Mum’s voice was pitiful. “It’s going to end in disaster. I know it.”

David was as happy as me when he heard the news. He had just passed his driving test and offered to drive Granny to Southampton, where she was due to board her ship.

“It’s brilliant!” he grinned. “She can catch herself some rich old sheep farmer and we won’t ever have to see her again. Thank you, God!”

Eventually, Dad convinced Mum she couldn’t stop Granny from leaving, so instead, Mum focused her attention on getting everything ready for the trip.

For weeks, our lives revolved around Granny. Mum took her out for countless shopping trips, to appointments with the hairdresser, chiropodist, dentist, or to have her inoculations.

The contents of her flat had to be sorted and packed and the furniture taken to the auction rooms to be sold. Granny insisted on spending every penny she had on new clothes. There were evening gowns, day dresses, high-heeled sandals and even an emerald-green swimming costume with white lacing.

When Mum tried to persuade her to save some cash for an emergency, Granny ridiculed her. She was certain that, once she found her new man, money wouldn’t be a problem.

When the day of Granny’s departure arrived, Dad and David took it in turns to drive the car to Southampton. Granny sat, squeezed between Mum and me, on the back seat, wearing an enormous black hat with a wide brim to protect her complexion from the Australian sun. It was a long journey.

Finally, we arrived at the port, and Dad found a trolley. He wheeled Granny’s trunk to the departure hall, and she tottered behind him while Mum, David and I pulled the rest of the luggage from the boot.

By the time we had carried everything into the departure hall, Granny was nowhere to be seen.

“She’s gone to check out her cabin,” Dad said. “I expect she’ll be back in a minute.”

A porter took away the rest of her luggage and we sat down to wait.

An hour later, an announcement told us that the gang planks were being removed so we went out onto the harbourside.

I was awed by the size of the liner. It loomed over us like a tower block, all shining paint and chrome railings. Excited travellers leaned down, waving their farewells to friends and families standing around us.

Mum shielded her eyes with her hand as she tried to pick out Granny among the faces high above us.

But she was not there.

Thirty minutes later, with a blare of sirens and a huge churning of seawater, the mighty vessel slid away from the dock and headed out to sea.

Mum stood for a long time, watching it go.

“I thought she might at least have waved goodbye,” she said at last.